Awkward Penguin Comics

Awkward Penguin Comics

|

|

To begin, let’s not fall into the trap of seeing these comics as mere distractions, as random funny bits. The very awkwardness of these penguins holds a mirror up to the fundamental awkwardness of human subjectivity itself. These penguins do not simply fail at some task, they embody failure. And isn’t this the condition of modern subjectivity? We live in a world where things are constantly breaking down—ecological collapse, economic crisis—and yet, we continue, awkwardly, pretending that everything can still work. These penguins are not simply bumbling through absurd situations; they are navigating the very collapse of meaning, much like we are.

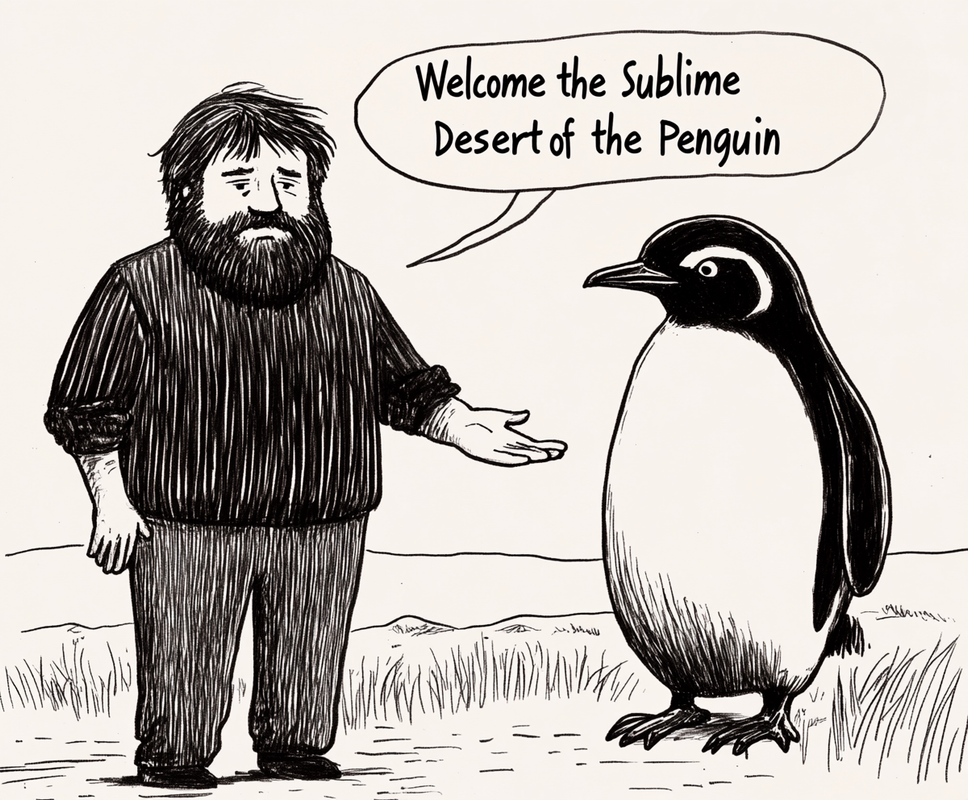

Think, for example, about how language fails in these comics. Lacan would say that language always misses the mark—it can never fully capture the Real, that part of existence that escapes symbolization. In one moment, a penguin says “woof” to a lobster, and isn’t this a perfect representation of how absurd our attempts to communicate with the world truly are? The world resists our efforts to make sense of it. The penguin’s “woof” is a moment where language collapses, revealing the void at the heart of communication. But this is not just funny—it’s deeply unsettling. We, too, are constantly trying to speak into the void, using language to mask the gap in our understanding of reality, but the Real always intrudes. The penguin’s awkward attempt at speech is our own awkward attempt at making sense of a world that cannot be fully grasped.

But this awkwardness also reflects our relationship to desire. Lacan taught us that desire is never about simply obtaining what we want. It’s about maintaining a certain distance from the object of desire. If we get too close, the whole structure falls apart. In one comic, a penguin is excluded from being poisoned because “he’d like it too much.” This isn’t just a gag—it’s a perfect encapsulation of how desire works under capitalism. The system offers us poison, but we are only allowed to want it just enough. The moment we fully embrace it, when we enjoy it too much, we threaten to collapse the entire edifice of desire that keeps capitalism functioning. This is the same structure that keeps us consuming, keeps us invested in the very things that exploit us. The penguins’ awkward handling of desire reflects the awkward way we engage with the poisonous pleasures that capitalism offers us.

And then we must confront the issue of repetition. The penguins live in a world of endless repetition—explosions, disasters, and yet nothing fundamentally changes. This is not just a comic device; it’s a reflection of our own numbed existence. We live through constant crises—financial meltdowns, ecological disasters—and yet we treat them as routine. When a penguin remarks, “It must be Wednesday,” we’re not just laughing at the penguin—we are laughing at ourselves, at our own inability to react to the repetition of catastrophe. Freud’s concept of the repetition compulsion is key here: we repeat trauma, not because we enjoy it, but because we are stuck in it, unable to escape. These penguins are showing us the structure of our own trauma, how we live through repeated crises without ever breaking free from the loop. The awkwardness of their existence is the awkwardness of our own entrapment within a system that keeps failing, and yet continues.

And what about history? Look at how the penguins engage with historical references—whether it’s Seduction of the Innocent or Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. These moments are not just parodies; they are reflections of how history itself has been commodified, reduced to empty cultural signifiers. The penguin reading Seduction of the Innocent knows, on some level, that this critique of comics is absurd, yet he reads it anyway. This is precisely how ideology works today. We know that the media we consume is harmful, but we indulge in it anyway. The critique becomes part of the enjoyment. The awkwardness of the penguin reading this outdated moral panic mirrors our own awkward engagement with the critiques of capitalism and media—we know, but we continue to participate because the critique itself is part of the pleasure. The penguin isn’t just consuming a book; it’s consuming its own complicity in the very structures it critiques.

This is where the awkwardness of rebellion comes in. Think about the homage to Jack Kerouac’s On the Road—a text that was once the manifesto of countercultural rebellion. And yet, in the world of these penguins, the road trip is over, the car is wrecked, and they stand there, awkwardly, unsure of what to do next. This isn’t just a joke—it’s a reflection of how rebellion itself has been absorbed into the very system it once sought to oppose. The countercultural movement has become another product, another signifier that no longer holds its radical potential. The penguins, standing awkwardly in the aftermath of their failed rebellion, reflect our own confusion about what resistance even looks like in a world where everything, including revolution, has been commodified. Their awkwardness is the awkwardness of realizing that even the structures of resistance have been co-opted by the system.

This is how you must read awkward penguin comics. It’s not about going comic by comic, gag by gag—it’s about seeing the structures they reveal: the breakdown of language, the repetition of trauma, the toxic structure of desire, and the collapse of historical meaning. The penguins are us, awkwardly moving through a world that no longer makes sense, stuck in loops of failure, yet unable to stop. Their awkwardness is not something to laugh at—it’s something to laugh with, as we recognize the absurdity of our own situation. The laughter is the laughter of complicity, the laughter of those who know the world is falling apart, but who can’t help but continue waddling forward anyway.